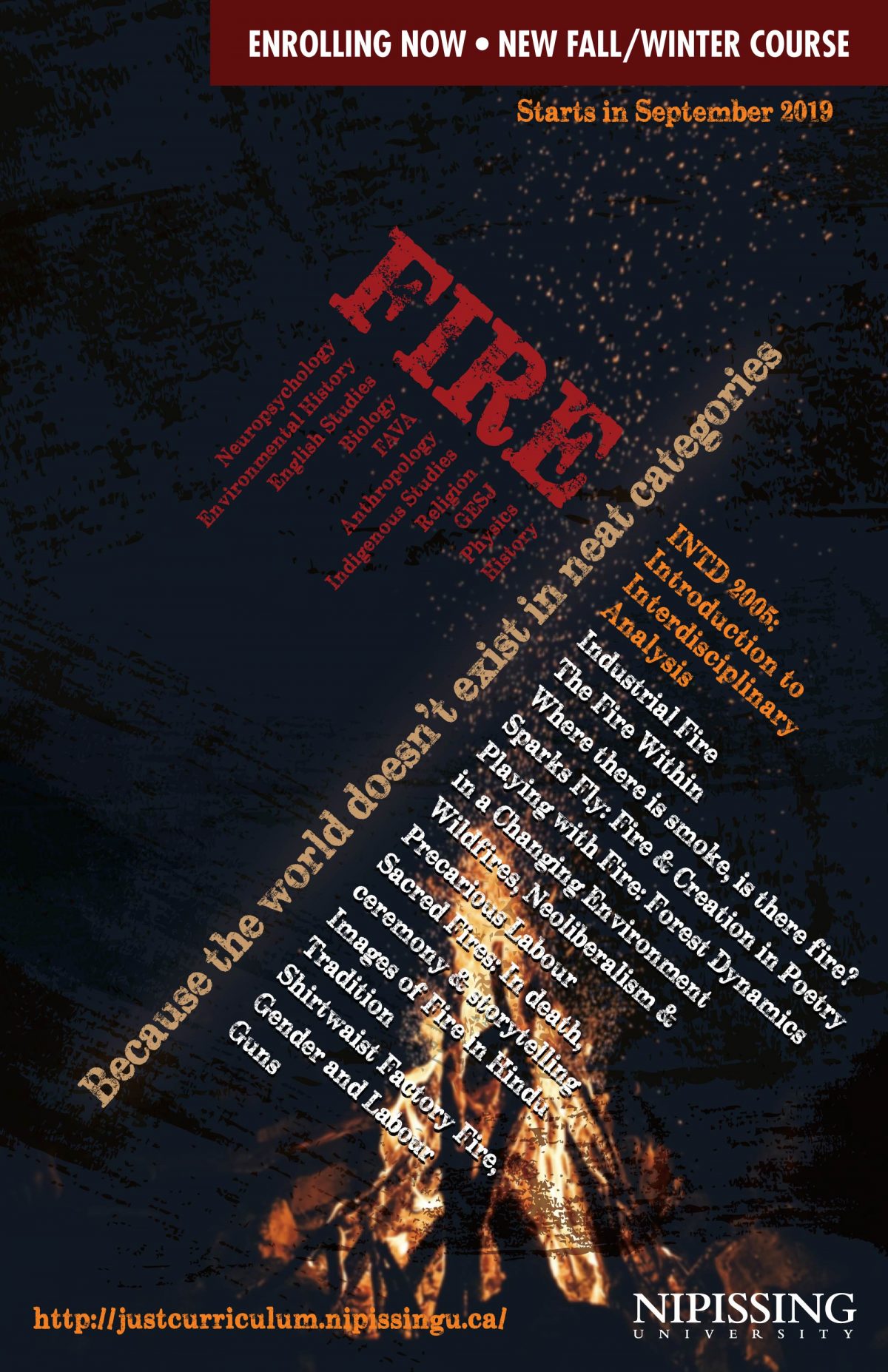

FIRE

Because the World Doesn’t Exist in Neat Categories…

FIRE in underway! This is our 8th Interdisciplinary Concept class and we are as excited as ever to see where this collaborative experiment in emergent knowing takes us all. As with all our INTD classes, while we can give you a sense of the journey, right from the start, we have no sense of the destination. This is one of the most unique things about these classes. We can’t really tell you what they are ‘about’ until it’s all over. So stay tuned and we’ll get back to you on that question. In the meantime, here’s the road map for the trip.

Erin Dokis Indigenous Studies

My focus will be on Nishinaabeg relationships with fire. In Nishinaabeg culture, men and women have different but equal roles and teachings about various aspects of our lives. For example, while women carry a responsibility for and teachings about water, men carry the responsibility for and teachings about fire. When talking about fire from the perspective of Nishinaabeg, it is important to demonstrate that balance so I have invited my brother Tyler to join me. Through storytelling Tyler and I will share our understandings of fire, as taught to us by our elders, our stories, and our experiences.

Dr. Andrew Weeks Psychology

Your Brain On Fire

This class will provide a basic introduction to the anatomy and function of the human brain. The theme of ‘Fire’ is ideal for this discussion in a way because at a basic level the brain helps us decide whether to approach or avoid things. Experience with and memory of various type of fire, in the literal sense, shapes whether we enjoy it or fear it in various contexts. Is it a pleasant memory of a campfire or a raging out of control forest fire that comes to mind when the word ‘Fire’ is presented? What parts of the brain handle these memories and feelings? How did we learn to use fire as a tool for cooking and warmth? How do you recover if you’ve been caught in a burning building? These and other questions will be explore in relation to your brain and how it functions.

Dr. Jamie Murton Environmental History

From Every day to Industrial Fire

Fire was once an everyday thing, a common tool. A fire map of the central plains of North America in the 19th century, fire historian Stephen Pyne has pointed out, would have shown fire everywhere, lit by settlers and indigenous people for clearing land and for insect control, burning in forges, in hollowed out stumps full of charcoal, in stoves and, sometimes, in forests. Now, fire is still central to the existence of our industrial society, but it is hidden, banished from cities and encased in fire boxes and engines. We tend to think of nature as separate from humans, and of the human impact on nature in terms of destruction. Fire forces us to rethink that. Fire in nature is both creator and destroyer, burning grass and forests so new plants can come up. Its occurrence on earth is tied to human activity, humans being largely in control of the means of combustion and responsible for shaping the landscapes where fire can and cannot occur. Considering the history of fire from fire as a common tool to industrial fire, as this talk will do, shows us the complexity of the human relationship to nature itself.

Dr. Gillian McCann Religions and Cultures

Fire in the Hindu Tradition: God, Messenger and Witness

It can be argued that fire is the central metaphor within the Hindu tradition. This religion, which has been practiced continuously for over four thousand years, has engaged intimately with fire in both its concrete and symbolic forms. Traditionally a fire would be kept burning at all times within a Brahmin home and we find mention of it in the earliest sacred texts. This lecture will offer an overview of the Hindu concepts of fire from the Vedas, the practices of yoga and Ayurveda, to the feminist films of Deepa Mehta.

Dr. Jeff Dech Biology

Playing with fire: how scientific reasoning has revised ideas about forest management in a dynamic environment

Fire is a pervasive natural disturbance that has shaped the development of the biosphere over millions of years. For most of that time, variation in fire activity was driven by the interaction of climate with vegetation; however, human activities in the most recent millennia have exerted a strong influence on these systems, thereby altering fire regimes across the globe. In North America, historical changes in the frequency, intensity and extent of forest fires have been documented throughout the continent, and these have coincided with changes in patterns of land use and management of forests. These changes have been particularly rapid during the 20thcentury, following the advent of fire suppression policies and technologies.

After millennia of natural and anthropogenic effects exerted across broad spatial scales, the resulting mosaic of fire behaviour over space and time, and its subsequent effects on forest ecosystems, is not detectable using normal modes of human observation. From the point of view of forest ecosystems, processes are not directly observable at scales of sensory perception available to humans, which are limited in spatial (e.g. kilometers) and temporal (e.g. years) extent. Indeed, our perceptions of natural systems can sometimes be misguided by this myopic observational bias. Progress in the development of techniques that expand observational frameworks (e.g. aerial photography, remote sensing, tree and ice core sampling) have generated new opportunities to examine and understand the role of fire at ecologically relevant scales.

New opportunities afforded by novel observation techniques have revealed that the structure and function of natural systems is not always what it seems on the surface. Science proceeds by posing falsifiable hypotheses to explain observations and eliminating those that are unsupported by data. By posing scientific questions we can elucidate patterns and mechanisms that are contrary to our expectations. Following these approaches, forest ecologists have revised their understanding of forest ecosystem function, and proposed new approaches such as ecosystem-based management (emphasizing multiple values including social and cultural ones) and the emulation of natural disturbance regimes (following nature).

There are criticisms of the both the old and new paradigms. For example, traditional management of the boreal forest of Canada involves the pervasive use of clear cut systems based on the assumption that intense fires are the only disturbance of importance in these systems. Clearly the data suggest that this assumption is false. Nevertheless, a switch to an emulation forestry approach may be problematic, given that we lack reliable observations of the past disturbance regimes in these forests, and such observations may be a poor benchmark anyway, because the past is no guide to the future in a system exposed to significant climate change. One way to make some progress on this front is to further expand observational powers by using geochemical signals in charcoal to reconstruct patterns of fire behaviour. Such methods show promise for adding to existing sources of data that can be harnessed to test hypotheses about fire regimes and forest development in the past.

Dr. Katrina Srigley History

Death by Fire: Working Women:

Activism and the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911

Focusing on the history of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire of 1911, one of the deadliest industrial disasters in North American History, this lecture will explore this fire as a context for working and immigrant women’s activism. It will consider some of the workplace changes that resulted from the event, as well as the issues that remain ever-pressing amongst vulnerable workers the world over. As part of this process, we will examine primary sources generated in the aftermath of the fire, including interviews given by women who survived and trial transcripts, to consider what they tell us or don’t tell us about this historical event.

Dr. Nathan Kozuskanich American History

American Firepower

America is the most heavily armed society in world history with somewhere between 200 and 250 million firearms in private hands in a country of about 330 million. And yet, only about 30% of Americans say they personally own a gun, and about 40% of American report living in a household with a firearm—a number that has stayed more or less steady since the 1970s. Republicans (45%), men (43%) and self-identified conservatives (40%) are the most likely key subgroups to say they personally own a gun. Women (17%), Democrats (16%) and Hispanics (15%) are the least likely to report personal gun ownership. During this section of the course we will make sense of these numbers in historical context, paying particular attention to how the politics of race, class, and gender shaped the American gun debate and what the Second Amendment’s protection of a “right to keep and bear arms” has meant over time.

Professor Amanda Burk Fine Arts

Where there is smoke, is there fire?

Representations and use of fire in contemporary art.

Fire has been present in artmaking from its earliest beginnings. We see fire used in the production and animation of cave paintings, in the material transformation of clay into ceramics, and in the making of charcoal as a material used for drawing. Fire has always played a transformational role in art by physically altering materials. Grounded in this history of material transformation, we will examine how artists working today are using fire and smoke in their art practice, moving beyond material shifts, to transform our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Dr. Gyllian Phillips and Dr. Sarah Winters English Studies

Sparks Fly: Fire and Creation in Poetry

This lecture covers the ways in which three different poets from the seventeenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries use the imagery of fire to convey the vision each has of the self, the divine, and poetic creation. We close read the sonnets “Batter My Heart” by John Donne, “The Windhover” by Gerard Manley Hopkins, and “The Forge” by Seamus Heaney, setting them all in the context of a rich tradition of artists evoking fire to remake the world.

Professor Joe Boivin Biology

The Fire Within

What could be a more human experience than to sit beside a campfire, listening to the crackle of burning firewood? As you bask in the warmth and glow of the fire, you may not consider the chemistry happening in front of you. From a chemical perspective, burning wood can be described as the oxidation of sugar. Wood is mostly cellulose, a fibrous carbohydrate made-up of the sugar glucose. The fire’s heat breaks the cellulose apart, thereby oxidizing the glucose, releasing carbon dioxide and water vapour as byproducts into the air. Remarkably, the oxidation of glucose is also the process that keeps each of our cells alive. This talk describes the fire within: highlighting how life on Earth harnesses energy to drive all biological processes at the cellular level. In this basic overview of metabolism – the totality of an organism’s chemical reactions – we will also consider the food we eat and reflect on the fuel each of us consumes to keep our inner fires burning.

Dr. Reade Davis Anthropology

Raised and Razed from the Ashes?

Playing with Fire at the Beginnings and Ends of Worlds

The capacity to manage and control fire is frequently cited as a critical marker of human exceptionalism and an important driver of hominid evolution. By taking what had been an uncontrollable threat and bending it to their will, the story goes, our Homo Erectus ancestors gained tremendous advantages in terms of their capacity to keep themselves warm in cold environments, cook their food, protect themselves from potential predators and other dangers, and illuminate the darkness. This, biological anthropologists and archaeologists have suggested, set in motion a chain of events that eventually gave rise to the emergence of evolutionarily modern humans and their subsequent migration out of Africa to populate of the rest of the world. Other commentators have sought to extend this narrative further, arguing that continued developments in the capacity of humans to manipulate the power and energy of fire inevitably gave rise to plantation agriculture, cities, metalwork, and finally the fossil fuel age, each of which served to further “liberate” human beings from the constraints imposed by their environments. Yet, this triumphant story is just as noteworthy for what it leaves out, particularly the diversity of practices through which indigenous peoples around the world engaged with fire and the ongoing colonial efforts to suppress or eliminate indigenous practices and replace them with new ones, as well as the degree to which colonial expansion since the 16th century paved the way for industrial capitalism, which is directly implicated in the present environmental crisis. This class will endeavor to construct a critical counter-history of the relationship between fire and human civilization. Drawing upon the work of scholars of the Anthropocene, post-colonialism, and post-humanism, we will discuss the colonial ideas of mastery, linear progress, and externalized nature that are embedded in dominant Western European narratives, and some of the consequences these ideas have had for other ways of knowing and being in the world. Furthermore, we will explore the degree to which rapid climate change produced by dependence on the fossil fuel economy, coupled with neoliberal policy reforms in recent decades, have created unprecedented vulnerabilities for humans and non-humans alike.